Living into the Promise

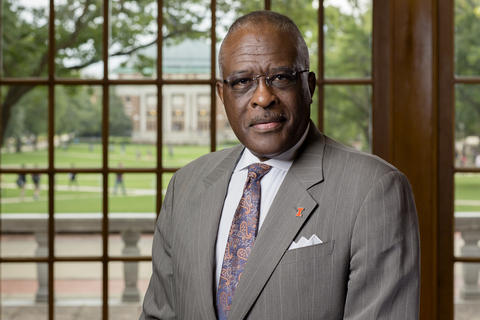

The University of Minnesota Urban Research and Outreach-Engagement Center (UROC) was five years old when it hosted a Community Day ceremony with then-President Eric Kaler, naming the research center in honor of Robert J. Jones. Now the chancellor of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Jones recalls being “deeply humbled” to have his name forever tied with UROC. “I have always had much more than a passing interest in the center, but now I am permanently connected with the University and the community,” he explains.

An accomplished professor of agronomy and plant genetics, Jones spent 34 years teaching and doing research at the University of Minnesota. He also served as executive vice provost and senior vice president for academic administration from 2004 to 2013. It was in that latter role that Jones spent years working to make UROC a reality.

As a longtime North Minneapolis resident, and a believer in the idea that a land grant university should serve the community, Jones devoted himself to helping establish an urban outreach center on the city’s northside. Many challenges had to be overcome along the way but, in collaboration with others, Jones was able to build trust and strengthen the relationship between the University and community members so that UROC could officially open its doors in 2009.

As part of UROC’s 10-year anniversary celebration, we talked with Jones about how the center got its start. We also asked what role he believes urban outreach centers can play in these times of social and economic unrest. Here is what he had to say.

Chancellor Jones, why are centers like UROC so important, and what role should they play in these times of civil unrest?

Jones: First, I don’t think there are many places like UROC. The model is unique, and I’ve given presentations about its vision all over the world. I think the key role it can play is convening dialogs. UROC has the power to do that, and it can make that happen in one of the underserved communities in Minnesota because there is trust. After the George Floyd protests, now what? What is the call to action? We need to talk about fundamental reforms in policing and UROC could be a part of the strategic plan to address racial issues and create real change. It can be a source of genuine community-based knowledge and be a model for the rest of the world.

Tell us about how UROC came to be.

Jones: UROC grew out of few things that were happening when Robert Bruininks was president of the University. He really wanted to rethink how we engaged with the public. We had research and outreach centers scattered across the state as part of our land grant mission. But we didn’t have anything in urban areas. So we thought about taking a place-based approach and establishing a center in North Minneapolis that would house a child development center led by Dante Chicchetti. Cicchetti currently holds the McKnight Presidential Endowed Chair and is the research director at the University’s Institute for Translational Research in Children’s Mental Health.

Dante was already recognized worldwide for his work in child development, and he had a world-class treatment strategy for minimizing the need for foster care. We wanted to bring his talent here to support our community, which was experiencing high rates of children being placed in care outside the home. But when we held listening sessions to talk about the idea, some people were not excited about it. They didn’t trust the U because there was a long history of researchers coming into the community to get what they wanted and not giving anything back. I have to admit, the U had made a number of missteps over the years that made those conversations very difficult.

We made some good progress with support from community partners, but everything fell apart during the 2008 recession. Suddenly, there was no way we could fund the project, so Dante worked with the University to establish a campus-based research center instead. He’s done very well, but I still feel a great sense of loss that we couldn’t make that happen in North Minneapolis.

At the same time all of that was going on, the University was thinking of ways to transform the General College. We were thinking of closing it, but that was very controversial, and many in the community thought the idea was racist. Bob asked me to take the lead on what to do, and it was clear to me that change was needed because African American students had less than a two percent chance of graduating from the General College as it was structured, which was unacceptable.

The turning point came after a gathering President Bruininks organized at Eastcliff. We wanted to talk with several members of the African American community about the strategies we were considering. And one of the people in the meeting asked an important, fundamental question: What is the University’s urban agenda?’ Bob looked at me, and I looked at him, and we kind of shrugged because the truth was, we didn’t have one.

Those talks helped us see that we needed to change how we thought about outreach and partnership. Rather than having academics going out into the community doing research that was based on their own interests, we needed to be a part of the community and tap into their knowledge. We needed to be asking what they needed, and we had to find out what was important to them.

It couldn’t just be research for research’s sake. That was the old model. I didn’t understand that when people said it at first, but I finally realized that what they were saying to us was: ‘What is the point of your research in our community if it won’t bring about change?’ That’s why UROC’s participatory-action research must be translated into policies, jobs and education initiatives that transform the community. If that doesn’t happen, it’s just business as usual.

What was the vision for this new kind of center?

Jones: We didn’t have to invent a new model. We already had University Research and Outreach Centers (ROC’s) all over the state. We needed to establish a presence in the city because if we wanted to have an impact on the community, we needed to be in the community. To be clear, though, we didn’t want UROC to be a community center. We always wanted it to be a way of taking assets from the main campus and putting them in the heart of the community.

We considered different sites in North Minneapolis and chose the shopping center that UROC is in now. The U bought the building and spent over $2 million renovating it.

It was boarded up before the renovation started and people said that it would be vandalized, but it wasn’t. Nobody touched it and I think it’s because people were really excited about it. We had a big sign explaining what UROC was going to be and it became affectionately known as U Rock! We hired a minority-owned architect firm and construction company for the renovation, and they help made it what it is today.

Looking back, would you do anything differently to get UROC off the ground?

Jones: No, there’s absolutely nothing I would do differently. It’s absolutely amazing how the pieces came together with everyone working together to make it happen.

Is UROC what you envisioned it would be?

Let me be clear: I did not do this alone. I had tremendous support from Bob Bruininks, the board of trustees and community partners. And two faculty/staff members were the main anchors at UROC in the beginning, Craig Taylor, former director of the University’s Office for Business and Community Economic Development (who now works for Extension in Blue Earth County), and Professor Scott McConnell, a child development researcher. We all stayed the course when community conversations weren’t going well because we were all committed to seeing the outreach center be built. All of us believed that a contemporary land grand university should have some sense of responsibility for serving underserved communities.

I’m very pleased with all that’s been achieved, and we all know there’s more work to be done. I strongly endorse UROC's newly announced Research Agenda and corresponding request for research-based proposals. There needs to be an aggressive University-led strategy for economic development that attracts businesses to the community that can provide jobs. And after the murder of George Floyd, I believe now, more than ever, that there needs to be a very focused effort around racism and social justice. UROC was designed to be a microcosm of the University, place that addresses the community’s fundamental needs and I’ll tell you, there is nothing more important than those two issues right now. I'm proud to see UROC putting those issues front and center.