Mapping Prejudice

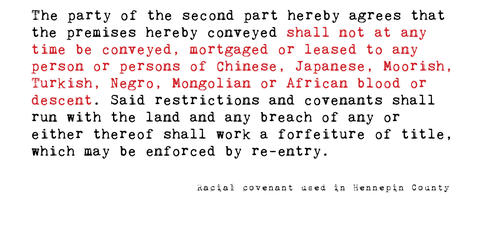

Racist restrictions, known as racial covenants, seem to have first appeared in Minneapolis property deeds in 1910 and become more widely used in the 1930s. While the wording varied, the intent was always the same: to prohibit the sale of homes to non-white residents, particularly black people. Challenged in court and finally made illegal in 1953, the covenants served, in many cities, as a very effective “hidden system of American apartheid,” says Kirsten Delegard.

One of the co-founders of Minneapolis’ Mapping Prejudice Project, Delegard is working with a small team of scholars, activists and students at the University of Minnesota to raise awareness about these little-known racially discriminatory deeds. Most importantly, she wants people to know that the damage they did is far from over. “The clauses in those deeds were among the most powerful instruments of racial segregation in U.S. history,” she says, explaining how few people know about them because they were a behind-the-scenes form of racism. “Instead of using mobs and burning crosses to keep black people out of white neighborhoods, they just made it illegal for them to live there.”

Speaking as part of the panel featured at the University of Minnesota Urban Research and Outreach-Engagement Center’s (UROC) October Critical Conversation on Racism, Rent and Real Estate, Delegard stressed how, because the racial covenants stated that properties could not be sold, leased or in any way transferred to people of color, the deeds not only led to the housing segregation that persists in Minneapolis today. They also created lasting financial disparities by depriving non-white residents of the opportunity to build wealth through home ownership.

While the project’s findings confirm what many people, especially Northside residents, already suspected, hearing the specifics has been eye-opening and emotional for others. “I give these talks and there are always people who feel like, ‘Duh, of course something like that was happening,” Delegard recalls. “But younger people of color sometimes cry and say things like ‘I thought my family was crazy or paranoid, or that they were making excuses for why things weren’t better. Now I see that they were right.’ Families have been blaming themselves for so long when inequities between people of color and white people in Minneapolis were engineered a long time ago, and we are still living with that today.

That’s why, beyond the academic aspects of the Mapping Prejudice Project, the larger goal is to highlight the effects of structural racism and the need for some kind of redress in the form of policymaking and reparations. “I think the big question is, what are we prepared to do about this now?” Delegard says. “We are showing with this work how we got to this place of extreme disparities, and I don’t think those disparities are sustainable. Knowing this history, we have to think about what to do about it.”

So far, Delegard and her team have found 15,000 deeds containing racial covenants in Minneapolis. But she is confident they will find many more. Once completed, their findings could lead to the first-ever comprehensive map of racial covenants in an American city. “Most people don’t ever see their deeds anymore, so they don’t even realize they contain racial covenants,” she explains. “Researchers have yet to find a community in cities and little towns across the country that did not have racial covenants. We hope this can be unmasked so people understand this was not an isolated thing. It is structural racism.”